Detachment Is All You Need

The following is an internal framework that helped me make better decisions through the ups and downs of my two-year startup journey. This post is more on the philosophical side. I’m sharing it because it helped me navigate the chaos and existentialism of startup life. I hope it helps other founders too.

Startups are chaos

More than anyone outside can imagine.

Things not working? Chaos.

Things working? Even more chaos.

There are so many moving parts that if someone looked at a founder’s life from the outside, they’d wonder how that person hasn’t lost their mind yet. And honestly? Many do. That’s why “exit and disappear to an island” is a thing. That’s why post-acquisition existential crises are so common. Founders who spent years in hyperdrive suddenly don’t know who they are without the company.

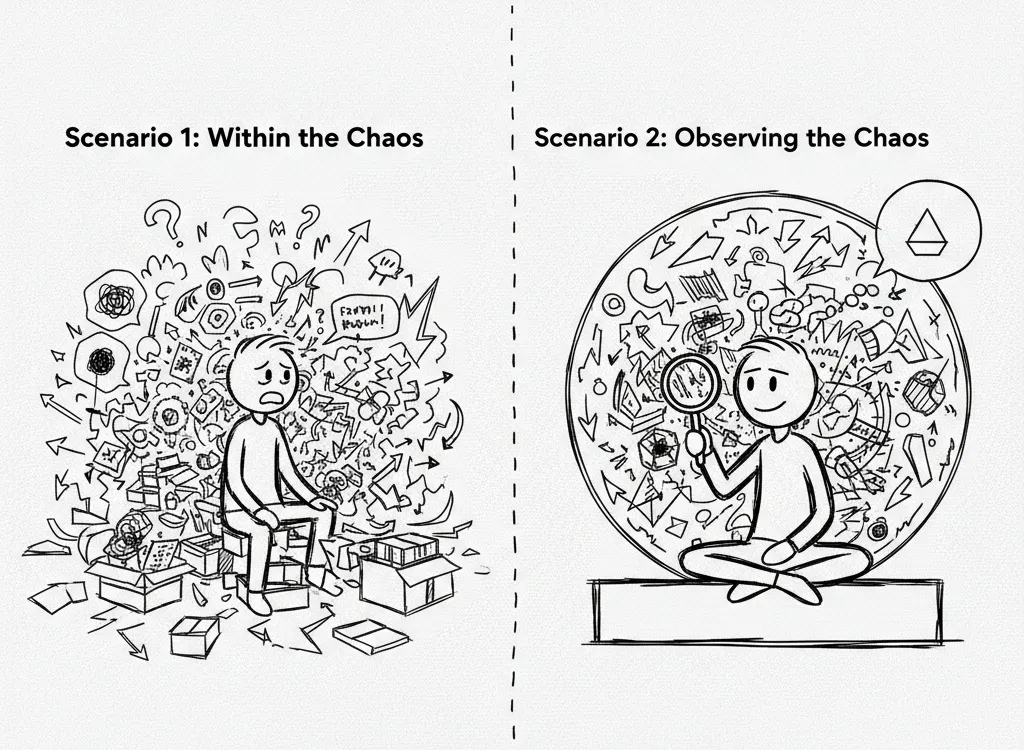

But here’s what I’ve learned: even when everything around you is chaos, the best decisions come from internal calm. No one thinks clearly in chaos. Clarity requires peace.

So how do you find that peace?

Detachment.

When you can observe the chaos as an independent, external observer, even while you’re in the middle of it, you develop this tremendous ability to remain unaffected by it.

What detachment actually means

Detachment doesn’t mean abandoning everything or not caring. It means being fully engaged while remaining emotionally unshackled from outcomes.

Think about The Mom Test. To practice it properly, you need detachment. If you’re too attached to your idea, you’ll never ask the hard questions that could invalidate it. You’ll unconsciously steer conversations toward validation rather than truth.

I read The Mom Test two years ago and still asked terrible questions for months afterward. Why? Because I was terrified of hearing something that would destroy what I’d built.

There is no Mom Test without detachment.

The same applies everywhere: pivoting strategies, firing people, killing features you spent months building, saying no to investors whose terms would compromise your vision. All these decisions require you to hold your work lightly enough to see it clearly.

How to practice detachment

The formula is simple but difficult: don’t derive your joy from the thing you want to detach from. Derive it from the process itself.

You shouldn’t be joyful after building a successful company. You should be joyful while building it.

Jensen Huang has been a dishwasher, a waiter, and the CEO of a trillion-dollar company. In an interview, he mentioned he gave his absolute best in each of these roles. The joy wasn’t in the status. It was in the doing.

Or look at Rick Rubin, the legendary music producer. He produces music not for commercial success but because the creative process itself is the reward. In his book The Creative Act, he talks about how some of his most celebrated work came from encouraging artists to ignore what would “sell” and focus on what felt true.

Consider how Jerry Seinfeld approaches comedy. He’s obsessed with the craft itself: the precision of language, the structure of a bit. The external validation is nice, but it’s not where his fulfillment comes from. That’s why he could walk away from Seinfeld at its peak and feel fine about it.

Being joyful is a skill to learn, like writing code, like learning go-to-market strategy, like pitching investors. And whatever you do while being joyful becomes play, even the hardest things. Even building a unicorn.

When you’re attached to outcomes, every setback feels like a personal failure. Every competitor’s win stings. Every investor rejection questions your worth. But when you’re detached and focused on the process, setbacks become data. Competitors become irrelevant. Rejections become filtering mechanisms.

You’re still working just as hard. You’re still committed. But you’re free.

And that freedom, that internal calm, is where your best decisions live.